Sustainability on campus: ATES

The academic year has started, and the sustainability blog is back! As a continuation of our last post of the Wageningen Sustainability Guide, we want to dive a little deeper into sustainability on campus, with special attention to the new Aquifer Thermal Energy Storage (ATES). The system provides the campus with energy and thereby significantly reduces the CO2 emissions. Even though the project has already been finished in July, let’s have a look at what it exactly is and how it impacts the campus.

What is ATES?

ATES (Aquifer Thermal Energy Storage) is part of the WUR’s energy transition plan which is focussed on saving and generating energy. The energy generation is currently happening through windmills and solar panels, and ATES will contribute to the saving of energy. With the installation of ATES natural gas consumption on campus will be reduced by 95% and gas-related CO2 emission will be reduced by 63%. A significant change which will help to move towards a campus that is free of natural gas [1]. Good to know, Aurora is now already the WUR’s first building which is completely free of natural gas [2].

How does it work?

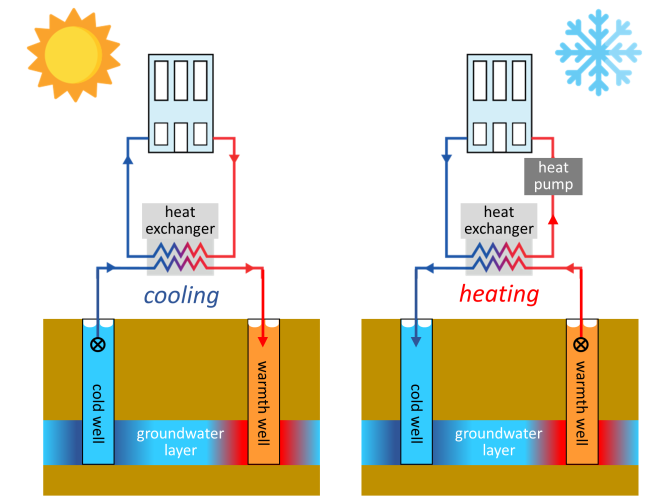

In principle, ATES allows for the storage of heat and cold in two wells that are installed in an aquifer (water-carrying sand package deep in the soil). A heat exchanger will help to cool or heat the water in the system, depending on the season, see figure 1. This means that in summer the water from the cold well can be used to cool the buildings. While in winter the water from the warmth well will heat the buildings with the help of a heat pump. The cold and warmth wells are interconnected with a loop, and allow for the cooled water from the warmth well to be stored in the cold well and vice versa [3].

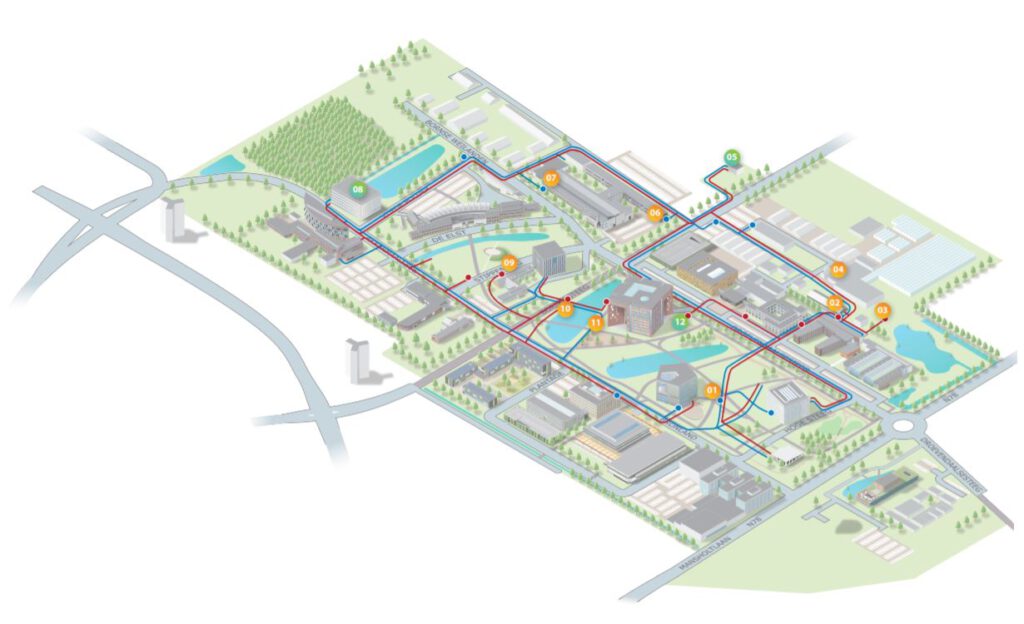

The construction of the ATES loop consists of different so-called ‘temperature streets’. These cold and warm streets allow the storage of warmth and cold from the different buildings, ready for reuse [3].

ATES on campus

The construction of ATES has turned some parts of campus upside down. Even though horizontal directional drilling prevented disturbance of the topsoil, it was inevitable to dig here and there. Nevertheless, the green restoration after construction added some biodiversity. Take for instance the slope of the pond along the Bornsesteeg. Despite the campus already containing many species that are important for insects, there is still too little food for i.a. bees in early spring. Thus flowering bulbs will be planted there this autumn which will bloom in early spring [4]. So don’t forget to walk by it in a few months to enjoy the new beautiful sight.

Furthermore, you could also do an ATES walk, see figure 2. It will take you all around campus, along interesting points of the system where it tests your knowledge on ATES and most importantly, you will stretch your legs during a well deserved break.

Want to know more about ATES? Read about the principle of the system here or about the green restoration after construction here.

By Sarah van Kooten